Fat Or Thin: Can The Bacteria In Our Gut Affect Our Eating Habits And Weight?

When we can’t lose weight, we tend to want to blame something outside our control. Could it be related to the microbiota – the bacteria and other organisms – that colonize your gut?

You are what you eat

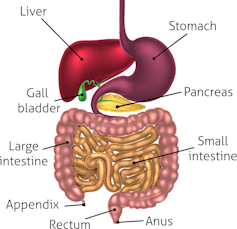

Our gut harbors some trillion microorganisms. These are key in harvesting energy from our food, regulating our immune function, and keeping the lining of our gut healthy.

The composition of our gut microbiota is partly determined by our genes but can also be influenced by lifestyle factors such as our diet, alcohol intake, and exercise, as well as medications.

What is the human microbiome?

The bacteria in the gut obtain energy for growth when we metabolize nutrients from food. So our diet is a crucial factor in regulating the type of bacteria that colonize our gut.

One key role of the gut microbiota is degrading the carbohydrates we can’t digest into short-chain fatty acids. This helps regulate our metabolism and is also important for keeping our colon cells healthy.

Changes in our diet can rapidly change the gut microbiota. Generally, a high-fiber diet that is low in saturated fat and sugar is associated with the healthier gut microbiome, characterized by a greater diversity of organisms.

On the other hand, diets high in saturated fat and refined sugars with low fiber content reduce microbial diversity, which is bad for our health.

Our animal studies have shown that consuming an unhealthy diet for only three days a week has detrimental effects on the gut microbiota, even when a healthy diet is eaten for the other four days.

This may be because the gut microbiota are under selective pressure to manipulate the hosts’ eating behavior to increase their own fitness. This may lead to cravings, akin to your system being “hijacked” by your microbiota.

Can gut microbiota changes lead to obesity?

Bacteria in humans fall into two major classifications: bacteroidetes and firmicutes. Obesity is associated with a reduction in the ratio of bacteroidetes to firmicutes but weight loss can reverse this shift.

Many studies have found that the gut of an obese person is more likely to contain bacteria that inflame the gastrointestinal tract and damage its lining. This allows the bacteria in the gut to escape.

We still don’t know definitively if changes in the gut microbiota from an unhealthy diet can contribute to obesity. Most evidence supporting this hypothesis comes from animal studies; for instance, the transfer of fecal material from an obese human can lead to weight gain in a recipient mouse.

One possibility is that the obese microbiota may be more efficient in harvesting energy, in part, by influencing the host to eat foods that favor its growth. This could ultimately contribute to weight gain.

Gut changes after weight-loss surgery

Bariatric surgeries such as gastric bypass, are one of the most effective treatments for obesity because they reduce the size of the stomach. This limits how much food can be eaten and has also been shown to promote the release of hormones which make us feel full.

But other factors may be involved. Intriguingly, some patients report a shift in food preference away from energy-dense foods after surgery. This may contribute to the success of the procedure.

Gastric bypass-induced weight loss has also been associated with increased diversity of the gut microbiota. But how much this contributes to the success of the procedure remains to be determined.

One possibility is that the changes in food preferences reported in bariatric patients may relate to changes in the composition of their gut microbiota.

How gut microbiota affect our behavior

Apart from regulating gut health, there is compelling experimental evidence that gut microbiota play a role in regulating mood.

Several studies have shown that depression is associated with changes in the gut microbiome of humans.

Depressed patients showed changes in their abundance of firmicutes, actinobacteria, and bacteroidetes. When these patients’ gut microbiota was transferred to mice, the mice showed more depressive behavior than mice that received biota from healthy people.

More work still needs to be done as it is unclear whether this may indicate a causal relationship, or be related to other factors associated with depressive disorders such as a poor diet, changed sleep patterns and drug treatment.

Depression is associated with changes in the microbiome. Fulltimegipsy/Shutterstock

Depression is associated with changes in the microbiome. Fulltimegipsy/ShutterstockEmerging evidence suggests that gut microbiota can influence other behaviors through the “microbiota-gut-brain axis”. Put simply, the gut and the brain communicate in part via the microbiota, which links the emotional and cognitive centers of the brain with our intestinal functions.

Recent work from our lab showed that rats consuming diets high in saturated fat or sugar, for just two weeks, had impaired spatial memory. These rats consumed the same amount of energy as the control rats (those on a regular diet) and were also similar body weight.

We found that the memory deficits were associated with changes in the gut microbiota composition and genes related to inflammation in the hippocampus, which is a key brain region for memory and learning.

Similar memory deficits have also been reported when healthy mice were transplanted with microbiota from overweight mice who had been fed a high-fat diet.

Together, studies such as these suggest the gut microbiota could play a causal role in regulating behavior. This may, in part, be due to the different microbiota profiles influencing the production of key transmitters such as serotonin.

What can you do now?

Further research is needed into the relationship between poor diet, gut microbiota, and behavioral changes. In the long term, such knowledge may be harnessed to develop targeted therapeutic interventions to replace relevant microbiota diminished by an unhealthy lifestyle.

Meanwhile, the good news is that gut microbiota can change relatively quickly and we have the capacity to promote the growth of beneficial bacteria which may ultimately improve a range of health outcomes. Eating a healthy diet of unprocessed foods, including adequate fiber, avoiding excess alcohol, and getting enough exercise are key.

Sources:

This article first appeared on The Conversation and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Authors

Margaret Morris