Could Fasting Or Ketone Diets Help Quash Cancer?

In animal experiments, intermittent fasting appears to slow the progression of certain cancers. Scientists are looking to see if a similar approach might help human cancer patients.

In one ongoing trial, research dietitian Michelle Harvie of Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust in the United Kingdom is testing the effects of a “5:2” intermittent diet that reduces intake to between 650 and 1000 calories on two nonconsecutive days every week, combined with exercise. She’s looking to see if it can slow disease progression in 67 metastatic breast cancer patients compared with 67 patients on exercise alone.

Another planned study by Dorothy Sears, an obesity researcher at Arizona State University, will look at the effects of time-restricted eating on breast cancer recurrence in a controlled, six-month trial. Earlier work by Sears and colleagues, published in 2016, followed more than 2,400 breast-cancer survivors. They found that women who routinely fasted less than 13 hours a night were 36 percent more likely to have recurrence within seven years than those who fasted for longer.

If fasting lowers cancer risk or dampens its progression, how might it do so? Some researchers think — at least in animal models — that weight loss and lower blood levels of insulin might be responsible, since insulin can promote cancer-cell proliferation and tumor progression.

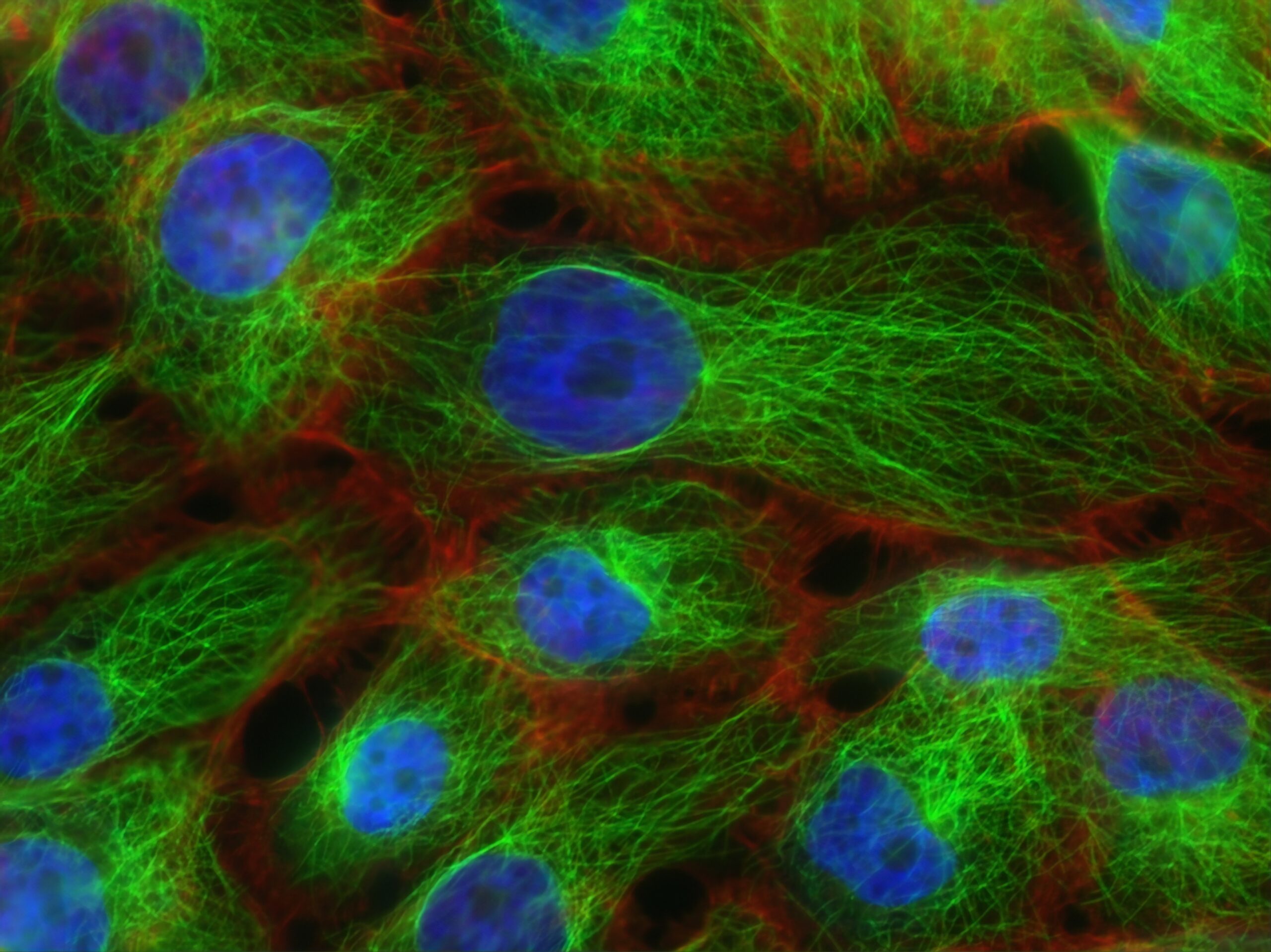

Others think one factor might be the high ketone and low glucose levels that result from fasting. That’s because cancer cells are often unable to process ketones for energy, due to deficiencies in their mitochondria. They obtain most of their energy via a process that doesn’t need oxygen: one that is less efficient than normal respiration and requires the cells to take up more glucose than regular body cells do.

Some believe it’s even possible that a high-fat, very low-carb ketogenic diet, which keeps sugar levels low and ketone levels high, might shrink tumors by withholding the glucose they need for survival. Biochemical geneticist Thomas Seyfried of Boston College (who had been using a ketogenic diet to treat patients’ epileptic seizures) examined effects of a ketogenic diet on cancer in mice. In 2003, his group reported that giving mice with brain tumors called astrocytomas a calorie-restricted low-carb ketogenic diet for 13 days slowed tumor growth by as much as 80 percent. The lower the blood sugar levels and the higher the blood ketone levels, the greater the effect.

Seyfried also hypothesized that because starving the cancer cells puts them under stress, they might be more vulnerable to chemotherapy and radiation. If so, doctors could use lower doses that have fewer side effects. He has been collaborating with doctors in Turkey, Egypt and other countries to test the idea. (The regimen often starts with a complete fast for several days to get ketone levels up and blood sugar down, which would likely not be recommended by standard-of-care guidelines in the US, he says.) Seyfried now thinks that chemotherapy or radiation may not be needed at all if the tumors are also simultaneously deprived of glutamine, which is another essential fuel for them.

But without solid evidence from clinical trials, the approach remains controversial. “There are some promising data, but more robust trials are needed,” says Antonio Paoli, who studies the health effects of nutrition and exercise at the University of Padova in Italy.

Some trials are testing a ketogenic diet plus radiation or chemotherapy for cancer, but almost none have reported results yet. One published report in malignant glioma patients found the regimen was feasible to follow but provided no survival benefit; in another trial, completed but still unpublished, neuro-oncologist Jaishri Blakeley and colleagues at Johns Hopkins University have tested the tolerability of a modified ketogenic diet and fasting in 25 glioblastoma patients following chemotherapy and radiation.

Oncologist Jutta Hübner of Jena University Hospital in Germany warns that the ketogenic-diet approach to cancer treatment might harm patients by causing weight loss or micronutrient deficiencies in people who are frail to begin with.

Others, like neuroscientist Dominic D’Agostino of the University of South Florida, argue that the potential side effects of the ketogenic diet are minor, especially when considering that cancers like glioblastoma are essentially 100 percent fatal. “We have to view this in that context,” he says.

Editor’s Note:

10.1146/knowable-012821-2

Author:

Andreas von Bubnoff

Andreas von Bubnoff is a freelance science writer and professor of science communication based in Germany. He drinks his morning latte in a beer mug and likes to have breakfast at noon.